The Loggia and the Sistine Chapel are probably the best known early fresco paintings that are recognized today, but fresco wall decoration was not a new idea when the Vatican contracted hundreds of talented professionals during the main period of embellishment, during the 15th to 17th centuries. Pictures were painted on walls for thousands of years before this.

The Loggia and the Sistine Chapel are probably the best known early fresco paintings that are recognized today, but fresco wall decoration was not a new idea when the Vatican contracted hundreds of talented professionals during the main period of embellishment, during the 15th to 17th centuries. Pictures were painted on walls for thousands of years before this.Raphael's frescoes at the Vatican were revered from the time they were painted early in the 16th century. 150 years after their creation, from

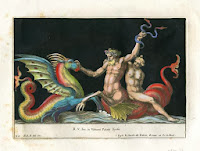

1670-1677 Pietro Santi Bartoli (1635-1700) endeavoured to capture the beauty and essence of Raphael’s classical frescoes of maidens and men, centaurs and other mythological elements, from the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

A century later, Swiss architect and engineer Domenico Fontana (1543-1607) was responsible for much of Rome’s redevelopment. In 1600 he accidentally discovered the buried region of Pompeii during tunnelling for the construction of a viaduct. Not then identified as a great municipium, dedicated excavation of these ruins did not begin until 1748 - and haphazardly continued for the next 112 years.

Another great municipeum of the 1st century, Herculaneum was not discovered until 1709 when men digging a well uncovered a decorated wall of the city. A town had been built above it, so excavation did not begin for 30 years. Artifacts and decorated walls from Pompeii and Herculaneum were illustrated as they were uncovered. Engravers were employed to transpose them onto plates for prints to be made to circulate the findings.

Some of the finest classical

engravers of the day were employed to engrave the frescoes for the most

important 18th century archaelogical work Le

Antichita di Ercolano Esposta (The Antiquities of Herculaneum

Exposed), published in Naples between 1757 and 1792.

Some of the finest classical

engravers of the day were employed to engrave the frescoes for the most

important 18th century archaelogical work Le

Antichita di Ercolano Esposta (The Antiquities of Herculaneum

Exposed), published in Naples between 1757 and 1792. Some of these wonderful

copperplate engravings have cross-hatched shaded sections to show where paint or mosaic had been destroyed - and remind us of their source.

Some of these wonderful

copperplate engravings have cross-hatched shaded sections to show where paint or mosaic had been destroyed - and remind us of their source.

Not only is it amazing that these frescoes survived and were rediscovered, it is also amazing that the fine engravings depicting them survive today. They are, after all, "just pieces of paper" as someone pointed out the other day. These beautiful antique prints represent art forms from hundreds of years ago.

Before modern technology, circulation of any information had to be carved or drawn onto a plate for printing. (For more information on these early printing methods check out our website Library http://www.antiqueprintclub.com/t-library.aspx.)

If you would like to see and perhaps own your own beautiful 18th century classical artwork, please return to our website at http://www.antiqueprintclub.com/c-22-classicaldesign.aspx or better still, see them exhibited at the Brisbane Antique Emporium, 794 Sandgate Road in Clayfield - open every day unless a public holiday.

Before modern technology, circulation of any information had to be carved or drawn onto a plate for printing. (For more information on these early printing methods check out our website Library http://www.antiqueprintclub.com/t-library.aspx.)

If you would like to see and perhaps own your own beautiful 18th century classical artwork, please return to our website at http://www.antiqueprintclub.com/c-22-classicaldesign.aspx or better still, see them exhibited at the Brisbane Antique Emporium, 794 Sandgate Road in Clayfield - open every day unless a public holiday.

No comments:

Post a Comment